route 66 and other kicks: plus what i read in july and august

Last week was seriously culture-packed. It made me happy to

live in L.A., grateful to know so many artists and arts lovers, and a little tired.

On Thursday Bronwyn and I ate the only non-meat items

Phillippe’s serves, then walked across the street to Traxx, the dinky bar at

Union Station that Chiwan Choi has turned into a pop-up literary hub this month. One of my favorite writers, Myriam Gurba, read a moving essay about her

schizophrenic uncle and showed slides of her face Photoshopped onto famous pictures and famous people. Myriam as ET, Myriam as Kim Kardashian. Her work

lives at the intersection of funny, intense, weird and joyful.

Mari Naomi presented a graphic personal essay—meaning a

personal essay in graphic form, like with drawings, not an essay with a bunch of

severed heads in it—about a troubled guy she’d dated. Then a real-life troubled

guy wandered into the bar and started standing super close to her and kind of

harassing her. (Must be a Union Station thing.) One of the show organizers very

gently and very heroically led him away, as all of us stood there watching it

like the world’s most uncomfortable TV show. It was a strange

life-imitating-art-or-something moment, but it could have been a lot worse.

Friday AK and I got a rare opportunity to see Ben Folds and

Elvis Costello from box seats at the Bowl. We would have happily watched grass

grow from box seats, but I love Ben Folds and loved him more after he played

the piano with his whole body and gave a sweet speech about supporting your

local symphony. I think Elvis Costello might be one of those artists who is

culturally adjacent to everything I love, but whom I don’t quite love. I dunno.

I like his songwriting, but his voice is a little too talky/crooner-y for me.

But still: really good company and did I mention box seats?

|

| Ben Folds, can I be one of your five? |

|

| Ed Ruscha en Route. |

I Tweeted something about how the Autry had free parking—it

really is the Wild West—and saw later that the museum had re-tweeted it, and

then my family thought I was one of those obsessed social media types.

I didn’t read that much these past couple of months. I’m in

the middle of a lot of books. My palette is persnickety lately.

The Snow Queen by

Michael Cunningham: I love Michael Cunningham

endlessly for asking the big questions--about life and death and art and God

and chance--and doing so in a beautiful way. The story's protagonist, a

middle-aged gay dilettante (or a Renaissance man who doesn't need to prove

himself to the corporate Man, depending how you look at it), also asks these

questions after he sees an ethereal, sentient light in the sky one night.

Shouldn't it mean something? If he *applies* the meaning, is it still real? Is

it responsible for saving his sister-in-law's life? Will it notice his and his

brother's selfish, petty wishes and punish them accordingly? I'm always trying

to parse God Is Love/Meaning vs. Everything Happens For A Reason (which I don't

buy). So I appreciate Barrett's endeavors. Nevertheless, the novel feels

slight. I like it more if I think of it as a novella, but even then, a lot of

what we're told about the characters--like that the sickly sister-in-law is a

stand-in for their mother--seems to happen offstage, or it gets lost between

the big lovely descriptions and ideas. But even a three-star Michael Cunningham

book is a four-star anyone-else book.

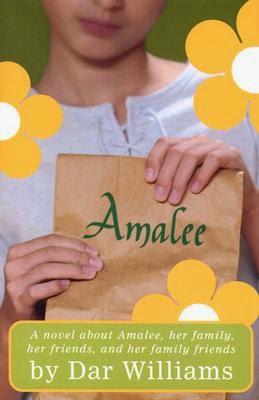

Amalee by Dar Williams: Like a lot of the over-ten crowd who read

this book, I picked it up because I'm a fan of Dar Williams' songwriting, which

is always clever and gentle and tells a story. Amalee is and does these things

too, but in a slightly less awe-inspiring format. This is a novel about an eleven-year-old's

relationships to adults in general, and to her father's gaggle of hippie-ish

friends in particular. I enjoyed it, but I also kind of understand why so many

YA books dispense with the adults at the outset. About two thirds of the way

through, Williams added subtle touches of magical realism to illustrate the

power of love in caring for a sick person. That was fun.

|

| Girl, interrupted, but with a tasty lunch. |

Rapp wrestles unflinchingly with topics no one wants to take on, but which most people must, to varying degrees: grief, luck, God or lack thereof, the impossibility of true empathy (although she seems quite empathetoc, never suggesting that her own staggering sadness is worse than other people's, despite her periodic thoughts along those lines).

I hate self-help books as much as Rapp hates sympathy cards with birds on them. They seem striving and mean, and indeed, one of the topics Rapp takes on is our culture's obsession with planning and achievement. Is it really more tragic when a child with "so much potential" is murdered than when a child with severe disabilities is murdered? What do we mean by the words that fall carelessly from our mouths?

Without being remotely prescriptive, this is the kind of book that actually *can* help the self. By trying to live in the world and experience her son for as long as he is in it, Rapp acknowledges her human struggles, big ones and petty ones, then sets them aside for the more important stuff. When people and institutions and thought systems crumble in their inadequacy, she'll simply say something like "(Rage.)" The book is rigorous and philosophical, poetic and kind. At its heart, though, it is a bit like the baby she describes: simple and true.

Comments