chavez ravine time machine

The thing I wish for the most, after the obvious,

much-blogged-about things, is the ability to passively time travel. I don’t

want to kill Hitler or my own grandfather, or warn the Titanic crew to bring extra lifeboats. I do want to watch history unfold like the best reality show ever. At

least once a week, I pause and marvel at the fact that I’ll never be able to see the original occupants of the houses I

walk past in Lincoln Heights, or know what L.A. looked like before white people

found it.

I feel this wish in my bones; it’s almost like regret. When

I imagine Heaven, I hope it comes with an endless, searchable DVR queue of

times and places. That said, I’d be satisfied with a queue limited to Southern

California in the last two hundred years. Maybe I’m self-centered, or just lack

the imagination to muster curiosity about ancient Rome, but I most

want to witness the here and now just before it became now.

Until we figure out how to do that Matthew McConaughey

bookshelf trick* in real life, I have Chavez Ravine, 1949: A Los Angeles Story by Don Normark. For those of you

unfamiliar with L.A. history or urban planning’s hall of shame, Chavez

Ravine—the scoop of land that now cradles Dodger Stadium—used to be home to

three poor, semi-rural Mexican-American neighborhoods. The roads were unpaved.

Kids went barefoot. Rain made a racket on the tin roofs of small unpainted

houses.

|

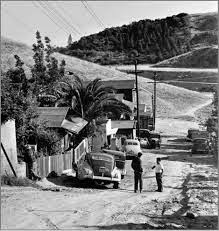

| Packards and palm trees. (Actually, I don't know if these are Packards. But alliteration!) |

However, public housing foes were freaked out that

Communists would somehow sneak in under this clause, and so they killed the

project. The once-tight communities remained scattered; the final few houses

were auctioned or burned. In 1957, the city council sold the land to the

Dodgers.

|

| Portrait of resistance in mariposa pants. |

|

| This girl and her doll do not take any shit. |

I bought an extra copy of Chavez Ravine, 1949 so I could cut out the pictures and use them as

prompts for my creative writing class tomorrow. Maybe some of them will

recognize Dodgerland before it was Dodgerland. Maybe they’ll see a little bit

of themselves in the photos, or maybe they won’t. Maybe they’ll be interested

to learn, as I did today, that the neighborhoods of La Loma, Palo Verde and

Bishop were as tight-knit as gangs, but without the consequences of drugs and

guns.

|

| Kicking it in front of Genaro's store. |

Kate: We lived at 707 Phoenix Street. The Ortiz family. We

were notorious.

Connie: No. That’s not true, don’t say that.

Chavez Ravine was also home to los viejitos, old white men who lived alone on the steep outskirts

of the ravine. Normark points out that, because they didn’t have families,

their stories are largely lost, which made me sad. Stories are immortality.

|

| Viejito y gato. |

*Just a little Interstellar reference there. Good movie. And silly. But moving and well-acted. I just kind of wish that Brit Marling had gotten her hands on it instead of Christopher Nolan.

**I buy most of my books on Powells or Indiebound, but I

knew I wanted two copies of Chavez

Ravine, 1949 so I cheaped out.

Comments

http://www.solanocanyon.org/blog-posts/may-24th-2015

Leonard Nadel took extensive photographs of the three old neighborhoods. You can see that here:

http://bit.ly/VLTCbX

I enjoyed your blog post!