a well behaved woman does a small right thing

My friend Sierra and I decided to borrow some writing prompts from Cheryl Strayed. The first one was: Write about a time you did the right thing. Here goes.

First, let me say this: I’m a goody-two-shoes. Or I was. I

was so good that my sister and I used to sigh when we saw bumper stickers that

said Well behaved women rarely make

history. There went our chance for fame.

Arguably, I have a ton of Doing The Right Thing examples

to choose from. Except I haven’t done the right thing so much as I’ve not done the wrong thing. I’ve never

dropped out, blacked out, abandoned, cheated, or stolen. But, in the words of

Stephen Sondheim, Nice is different than

good.

Doing the right thing, to me, means taking a risk or going

against the grain. It means behaving badly at times. For it to count (or at

least for it to make for good reading), something has to be at stake.

So here’s what I’ve come up with: I took a year off between undergrad and grad school.

So here’s what I’ve come up with: I took a year off between undergrad and grad school.

I know.

Both my parents had master’s degrees, and so did at least

one of their parents. If I have any cultural heritage, it is that I come from a

long line of nerds. My mom went to library school in part because she didn’t

date a lot. My dad got a physics degree partly because he’s somewhere On The

Spectrum, I suspect.

We have humble educations—state schools, all of us—but we

read and think and geek out hard. Back before the internet, one of my parents

was always jumping up from the dinner table to look up something in our musty

encyclopedia. My dad and sister have never put birthday candles on a cake that

didn’t require some kind of mathematical code to uncrack. The wax melts into

the frosting as they ponder whether the blue candles each count for ten and the

pink candles count for one, or whatever.

It was a given that I would go to college. Every year my

high school published a map showing where people were going to school. Being a

public high school in an upper middle class city in California, there were a

lot of UC’s, a lot of Cal States, a peppering of private schools and a long

list of people heading off to community college. There was also a short list of

people entering the military or the “workforce.” The latter struck us

college-bound kids as utterly alien and snicker-worthy. It might as well have

said “joining a cult.”

Midway through my run at UCLA, I figured I’d go to grad

school, too. I was thinking I’d study journalism, since I worked for the Daily Bruin. Then I read a Rolling Stone cover story about how

journalism schools were increasingly merging with media and communication

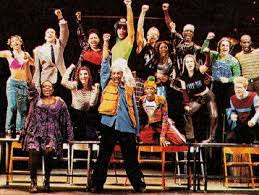

schools, i.e. PR. Purists that we were at the Bruin, we considered publicists to be the devil. I had seen Rent too many times to be a sellout, dammit!

So I turned to MFA creative writing programs. I wanted to go

to Columbia or NYU and live la vie boheme

but without the AIDS part. I also applied to the Iowa Writers Workshop because it

was at the top of U.S. News & World

Report’s list. I applied to San Francisco State and Cal Arts because they

were in California, and I liked the idea of going to an arts school.

|

| Viva la vie boheme! |

Then I got one acceptance letter, in a large envelope with

an orange-striped border. CalArts—a relatively new and therefore less

competitive program—wanted me.

|

| Hallelujah! |

They had a point.

Plus, imagine what they saw: A chubby blue-eyed 21-year-old

who dressed like a cross between a rave kid and 1972, who wrote precociously

but didn’t have much to write about beyond her own privilege-guilt. (E.g., in

my 1999 journal, you’ll find a long poem about the time some cholos rubbed up

on me at a Downtown club. You would have thought giving them the brush-off on

the dance floor was tantamount to Cortes destroying the Aztec empire.) It

wasn’t that I didn’t have “a story”—my own shit, my own trauma, my passions—but

I hadn’t discovered it yet.

|

| My race guilt and my internalized gender oppression did a pas de deux on the dance floor at the Mayan. |

School would have been a comfortable refuge, even if I had

to pay for it myself. But perhaps because the same parents who’d always taught

me to be good had also taught me to endure a certain amount of drudgery and

discomfort in the name of getting what you wanted, I knew that sliding directly

into grad school would have been too easy.

One afternoon I wrote an emotional letter to CalArts,

telling them I really and truly appreciated their offer, but I needed to go

live my life. I’d like to defer, I told them, although I imagined such a thing

wasn’t allowed. I put it in an envelope and sobbed in a heap on the floor of

the apartment I shared with three other girls.

(Three out of four of us were virgins. This feels like

relevant information. Also possibly relevant: the night I wrung my hands over

the fact that I’d learned Prop. 13 was bad for California, but I knew for a

fact my parents wouldn’t have had a second child if it hadn’t passed, thereby

lifting their tax burden, and I loved my sister! My roommate Stephanie told me

to calm down; her parents were Chinese, and she wouldn’t have been born if the

U.S. hadn’t bombed Japan and ended its occupation of China, but that didn’t

mean she was pro-nuclear-bomb.)

|

| The bomb will bring us together? |

I took my year. I interviewed for a bunch of dot-com jobs at

companies with names like Lemon Pop, who wanted to know if I could write

content about vampires. After a slow summer interning at Entertainment Weekly—during which I mostly watched the fax machine,

ordered lunch and read L.A. Weekly in

an office bigger than my current one—I began writing profiles of WB stars

(or “stars”) for Zap2it.com.

I occasionally worked weekends at Book Soup, a delightfully

crammed bookstore on Sunset, full of drunk and queer and homeless customers. I

nursed a crush on a wannabe TV writer named Nancy.

I nursed a waning crush on my roommate in the Miracle Mile,

a gay guy named Tommy who made Vietnamese spring rolls and said we should class

up our apartment by getting rid of our inflatable furniture.

I went dancing with my friends from Zap2it. I dated a guy

named Alex who liked attending weird Christian events ironically. I more or

less lost my virginity. I super-briefly dated a guy named Michael who was 31

and wanted to buy a house, and even though he turned me on to some good music,

I could not have been more turned off by the idea of dating someone with such a

boring name and such Republican ambitions as property ownership.

I earned $31,000 a year at Zap2it, and even though I still

hoarded used paper clips, it felt like a fortune. It was, in a way. Rent was

cheap (though we’d be priced out of the area two years later) and I had no debt.

I bought CD’s and second hand clothes from the dollar pile at Jet Rag on La

Brea. I bought a lot of caramel frappuccinos and sugary drinks at clubs. When

my 1987 Toyota Tercel broke down, my dad could usually fix it.

|

| You can get four items of clothing for the price of one frappuccino. |

I laugh at my 21-year-old self, but I laugh with affection.

I don’t see her as privileged and despicable anymore. My youthful naivete

walked alongside my youthful wisdom. I was just a dumb kid, but I was no dummy.

Comments