tops of 2023

I wanted to jump through my car radio and hug him, or some other useless action, because I believe so strongly that he is the exact father his children need and deserve, and at the same time, his line of thinking rings so true to me.

All of this is to say: 2023 was another year of mental struggle for me, in which I often felt lonely and anxious, two emotions that are deeply tangled for me in some preverbal corner of my brain. Why have a family if I couldn't be mentally and physically present for them? And, if I spent too much time dwelling on this possibility—a possibility that could be more like a probability if I lived in Gaza or Nagorno-Karabakh or Ukraine—would they or I some how disappear from each other's lives?

I am about to start Exposure Response Prevention therapy, which is the gold standard for OCD and similar anxiety disorders. As best I can understand it, it sounds like I'm supposed to sit there thinking about my worst fears, with no one comforting me or telling me it is very unlikely that I'll get pancreatic cancer anytime soon if at all, while another nice therapist charts my reactions and points to a dot on a graph that represents how fucked up I am. Given that my fears boil down to becoming a nonhuman number that no one wants to help, this all feels VERY MEAN.

More generously, I think ERP is supposed to help me let go of Big Fears so I can be present in my own life and the lives of people I love. I always thought that I was supposed to set aside small annoyances so I could focus on life's Big Meanings and Big Questions and, yes, sometimes Big Fears. But somehow that manifests as me turning small work mistakes into fears of cancer, and mistaking needing a nap for the end of the world. It makes me throw away small joys as if they're trash, when in fact they might be all we have. Is that the secret mature people have known all along? Is that why adults cry at kids' holiday performances?

It's hard to move forward when I'm not sure what kind of mindset I'm trying to cultivate. This all feels like some very frustrating growth I have to do before I can really be deeply creative again, or even as good at my job as I'd like to be. Making New Year's resolutions seems like hubris when I'm trying to find a new baseline. But if I can do my zillion therapy modalities, step up my mediocre eating and exercise habits, and write write write in the smallest little hen-scratch doses, that will orient me during this disorienting time, I think. I hope.

This Reductress headline has my number, so maybe I should note that in 2023, in addition to limping along mentally, I found a new job at a pretty great org one day before my severance ran out, and got to know Joey as Joey (a cuddly, funny, furniture climber) rather than a series of worries and question marks. I wrote a bunch of stuff for MUTHA and Publishers Weekly, and did some really fun book events at AWP. We visited with Joey's birth family and Dash's birth mom. I enrolled myself and my kids in new health insurance and found us new doctors, which took a thousand circuitous phone calls and made me cry. I did some long-ass solo parenting days so C.C. could get that much closer to getting her MFT. Sometimes we feel like ships passing in the night, but we are ships who still love and like each other.

Oh, and I read a fuckload of books, and watched some stuff. Here are some of my favorites.

Books

The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel: It wouldn't be a huge overstatement to say this is my platonic ideal of a novel. Ghost story, mystery, socially conscious epic spanning years. It's about the characters—complicit, innocent, and in between—who are affected by a Bernie Madoff-style Ponzi scheme. It's also about...life? Everything? Mandel does an amazing job of weaving threads and motifs and callbacks; I kept imagining a giant bulletin board full of cards and thumbtacks, to track it all the way they track crimes on TV. Coincidence drives perhaps too much of the plot (if it was good enough for Dickens...), but it didn't bother me. The way she plays with time—both on the page, as characters slip in and out of memory and alternate universes, and in terms of narrative strategy—is a lesson in technique. (Recommended by C.C.)

Carry by Toni Jensen: Jensen draws connections between interpersonal violence and sociopolitical violence in the most poetic ways, taking my breath away with knife-sharp wordplay and juxtapositions that feel like a form of protest art (because they are).

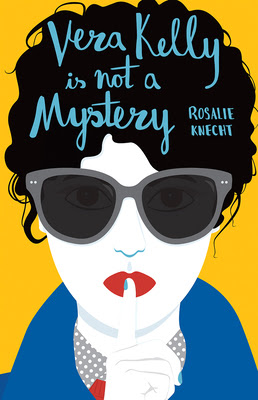

Vera Kelly Is Not a Mystery by Rosalie Knecht: As with the previous Vera Kelly novel, I devoured this book, and maybe loved it even more (I went on to read the final book in the trilogy as well; the second remains my favorite, but I was fascinated by how Knecht uses POV to show her protagonist's evolution). The plot follows Vera's foray into private investigation work, when she's hired to track down the nephew of a couple claiming to be exiles from the post-Trujillo Dominican Republic. As a former lost girl herself, Vera's loyalties are with the boy she's never met, not her clients. In the process, she discovers that the lone-wolf strategies that saved her when she was a teenager and a young CIA agent aren't working so well for her as a self-employed, late-twenties queer woman. The book takes place in 1967, long before the era of Brené Brown, which is perhaps why I found Vera's tentative steps toward vulnerability so moving. The stakes for trusting people in her line of work, in a time when she can be (and is) fired for being gay, are incredibly high. But that makes her leaps of faith that much more necessary.

Knecht has again written a moody, gorgeously described, character-driven novel with lots of intrigue and a queer couple I'm rooting for. (Recommended by Jennifer)

Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann: Given how dramatic this story is—murderous plots, moonshine, outlaw gangs, deep conspiracies, corrupt cops, cowboys, Indians, and J. Edgar Hoover—it's amazing to me that it isn't taught in every American history class. You could use this book as a tool to talk about the genocide-by-a-thousand-paper-cuts treatment of Native Americans, and about Osage resistance. The book also primes the pump for conversations about law enforcement and jurisdiction, and about our concept of a wild vs. settled West. But the fact that the story was buried for generations—though never forgotten by the Osage—speaks to how we treat much of Indigenous history.

As a Little House on the Prairie nerd (see below), I was particularly interested in Osage life in Kansas and Oklahoma in the 1920s, having last glimpsed the tribe on the move in 1869-1870, when the Ingalls family makes their homestead on Osage land before learning the territory hasn't been "opened" for settlement yet.

Worm by Edel Rodriguez: The scene that stuck with me in this graphic memoir that doubles as a cautionary tale about the creep of totalitarianism in the U.S. comes fairly early on. After much deliberation and considerable risk, Edel's parents have decided to leave Cuba as part of the Mariel boat lift in 1980. They live in limbo at a government refugee camp of sorts while they await the green light to leave. When it's finally go time, eight-year-old Edel is like "No, I'm in the middle of a baseball game with my new camp friends." That would 1,000% be Dash. It's moments like this that drive home the extent of global horrors—because the everyday challenges of life and parenting don't really stop. Kids still get bored. People still get on each other's nerves. But the stakes and the mental, physical, and logistical load are multiplied by a million. (ARC)

A Man of Two Faces by Viet Thanh Nguyen: Fierce, funny, genre-blending, and unapologetic, this memoir of Vietnamese refugee life in Northern California made a big impression on me (before Nguyen made headlines for getting weirdly cancelled at the 92Y author series for signing a letter calling for a ceasefire). Nguyen's "two faces" are that of a loyal son who is grateful for the opportunities he's had, and a rebel writer who interrogates privilege, colonialism, and American ideals. He does it all with fresh, savvy language that is a delight to read. (ARC)

Everything's Fine by Cecilia Rabess: Much of this story—bookended by the elections of Obama and Trump, respectively—reads like a romantic dramedy. Girl meets boy, girl and boy clash ideologically but slowly fall for each other over the course of careers in the financial industry, girl and boy breakup and reunite. She's Black, liberal, a bit of a party girl, and brilliant at math and puzzles. He's white, a fiscal conservative type, sincere, brilliant at money and making a lot of it. That kind of story (all the will they/won't they back-and-forth) could be a hard sell for me in the wrong hands, but Rabess sells me. Jess and Josh's personalities, communication, and the world around them are as complex as the story is (seemingly) simple. But the very, very end was not what I expected at all, and it turns the entire novel into a giant exercise in foreshadowing, in a way that is sneaky and chilling and brave. (Recommended by Shea)

Feeding Ghosts by Tessa Hulls: I'm realizing that at least seven of the books on my list are about generational trauma in some form. Is that my obsession, or is that humanity's legacy? I'm not sure. This beautifully etched graphic memoir tackles the topic most directly, as Hulls—raised in Northern California with her British dad and Hong Kong-born mother—explores her grandmother's harrowing escape from Mao's China, only to succumb to PTSD-induced mental illness. Her mother alternates between cold "ghost face" and the desire to trauma-bond with her daughter, who just wants to run away and become a "cowboy." I told a Chinese-American friend, who has a somewhat tense relationship with her mom, about the book and she said, "Omg, that's my family almost exactly. So much unprocessed trauma." The book unnerved me as I considered the impact of my own mental struggles on my kids, but it also performs healing in the most gorgeous way. (ARC)

I'm Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy: The structure of this memoir is deceptively simple: present tense, linear, lots of "show don't tell." This enables McCurdy to depict her abusive mom—who shoves her into a showbiz career, teaches her anorexia, and allows her no physical boundaries (to the point of sexual-ish abuse)—from the point of view of her childhood self for much of the book. In this way she shows why and how parental abuse is so complicated, because of course she deeply loves her mom and wants to please her. And because she tries so hard to please, she has no sense of who she is or even how to eat what she wants.

Later, she finds herself the hard way, by having unhealthy relationships with food, alcohol, and men. Appropriately, she never delves into her mother's backstory (I can't imagine she had an easy life either). A deep empathy dive would fail to serve her personal and narrative goal, which is to center herself and detach from her mother. Yet while her mother is a nightmare, she never seems more than or less than human, which says a lot about McCurdy's storytelling and her twenty-year character study of her mother.At one point, McCurdy says that acting always feels like a lie, and writing feels like truth. I hope she'll keep up her funny, candid writing, for herself and for her readers. (I'm not sure how I found this book; kind of just out there in the pop culture zeitgeist?)

The Little House books Laura Ingalls Wilder: This was the year that I reread all nine Little House books, an act that was both deeply comforting and often eye-opening, having last encountered them as a young kid. They're all fascinating portraits of settler colonialism at its most austere and even innocent, or maybe just ignorant. So much both/and in these books, along with the gorgeous descriptions I remembered: maple syrup candy made in the snow, printed name cards that were basically the TikTok of the prairie, the smell of wildflowers, oranges at Christmas, grasshopper plagues, bonnet strings trailing in the wind. (Recommended by Valerie Klein)

Honorable mention: Blow Your House Down by Gina Frangello, Whose Names are Unknown by Sanora Babb, Family Solstice by Kate Maruyama, Also a Poet by Ada Calhoun, The Jewish Deli: An Illustrated Guide to the Chosen Food by Ben Nadler

TV

Derry Girls: I heard it was great, thought the description sounded like a show I'd like, and somehow still waited years to watch it. And then I did and I loved it. There's a dissertation to be written about its parallels with Reservation Dogs—groups of semi-adrift teens on occupied land, whose primary concerns are still deliciously age-appropriate. The entire cast is wonderful, but I especially loved Saoirse-Monica Jackson as the constantly outraged Erin. Something about her face reveals how she is ambitious and righteously angry and completely ridiculous and self-centered all at the same time.

Fleishman is in Trouble: A smart portrait of the disappointments of adulthood and thwarted ambition, threaded with a clever examination of blame in relationships. The "Fleishman" of the title ultimately refers to both Toby—the almost insufferably "good" doctor protagonist—and his ex-wife Rachel, who disappears one day. Narrator Libby, a magazine writer turned SAHM, is in plenty of trouble too.

Movies

Barbie: As everyone has observed, this movie is funny and feminist, and toes the line between corporate critique and corporate shill. But it's also beautifully existential—it's more about human vs. doll than women vs. men—and fantastically weird.

Women Talking: Horrifyingly, this story of women serially raped by the men in their Amish-esque religious community, is based on a true story. The movie is, literally, mostly women talking—about who they are, what to do, and whether any of the younger men and boys in their circle can be redeemed—which distinguishes it from most other movies out there.

Leave the World Behind: I don't always love the moody post-apocalypse genre, but this one is really well done. The apparent terrorist acts—an oil tanker running aground, leaflets dropped from the sky by a vague enemy, a pool filling with lost flamingoes—are successfully creepy, but ultimately the source of horror and help lies in humans themselves.

Smoke Signals: Um, yeah, so this movie came out in 1998, but somehow I never saw it then. It's a moving Native American buddy/road trip movie and a story of how people can be both villains and heroes in the same lifetime.

Comments