elementary oppressors and what i read in december

When my best friend Bonnie and I were in fourth or fifth grade, we got shuttled off campus for GATE once a week, a baffling but fun reward for having scored well on some mysterious test back in second grade. Our mutual friend (and my former BFF) Stephanie was not in GATE. So what did Bonnie and I do? We invented an awesome girl from another school whom we’d befriended at GATE. Chonnie (as in Cheryl + Bonnie) was an amalgam of all that was cool in our ten-year-old minds, meaning she probably crimped her hair and did a lot of babysitting. We talked about her all the time, just to let Stephanie know what she was missing out on. We also made lists of all the things we had in common with each other but not with Stephanie, so that we could casually drop such gems as: “Names with six letters are really the best. Nine letters is just too long.”

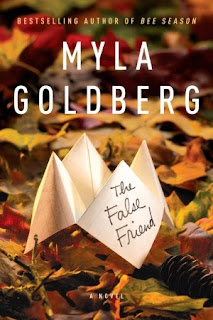

When my best friend Bonnie and I were in fourth or fifth grade, we got shuttled off campus for GATE once a week, a baffling but fun reward for having scored well on some mysterious test back in second grade. Our mutual friend (and my former BFF) Stephanie was not in GATE. So what did Bonnie and I do? We invented an awesome girl from another school whom we’d befriended at GATE. Chonnie (as in Cheryl + Bonnie) was an amalgam of all that was cool in our ten-year-old minds, meaning she probably crimped her hair and did a lot of babysitting. We talked about her all the time, just to let Stephanie know what she was missing out on. We also made lists of all the things we had in common with each other but not with Stephanie, so that we could casually drop such gems as: “Names with six letters are really the best. Nine letters is just too long.”These are the kind of mind games tween girls play with each other. Not all girls—AK spent her youth playing quietly with Star Wars action figures—but certainly me, certainly Bonnie, reluctantly Stephanie. And this is why I devoured Myla Goldberg’s The False Friend like it was made of very tart pie.

The heroine and could-be anti-heroine is Celia Durst, a woman in her thirties who, on her daily commute, has a revelation that the defining moment of her childhood didn’t go down the way she thought it did. When she was 11, her best friend Djuna disappeared when the two of them, plus three other friends, were walking home from school. Celia heads back East to confront the past and correct her remembered crime. What she discovers is a trail of smaller crimes, like breadcrumbs in the woods. Each mean-girl mission that she and Djuna led is random on its own, sadistic when stacked with their others. Celia discovers that Djuna’s disappearance has radically transformed all the girls who were there that day, one in a particularly unpredictable (but geniously woven) way.

One thing I’ve always loved about Goldberg is how kind she is to her characters, so it’s all the more interesting to see her write about a character coming to terms with the lack of kindness in her own earlier self. Reading the book, I felt guilty all over again for how Bonnie and I had behaved. And Stephanie didn’t disappear in the forest—she went on to be much more popular than either of us, and judging by her Facebook page, she has a very nice life now.

I should also add that while I was a bully for a year, that pyramid was quickly inverted as soon as I had an unwanted growth spurt, my hair frizzed and having a big imagination became less valuable than having a boyfriend. So while I related to Celia, I also related to Leanne, the beta dog who asks how high every time the cooler girls tell her to jump. In sixth grade, my “friends” formed a playground cheerleading squad that I willingly tried out for twice because according to their self-granted authority, I wasn’t up to par the first time. To possibly misappropriate the words of my Chicano lit professor, we are all the oppressor, we are all the oppressed. Myla Goldberg knows it.

Here’s what I read last month:

Major Pettigrew’s Last Stand by Helen Simonson: Review sequestered until book club!

Whale Talk by Chris Crutcher: I would be into reading a book about an adopted kid of color who relies on his athletic talents and pathological do-gooder tendencies to cope in a small racist town. The line between underdog and golden boy is an interesting one, which was a big part of what I loved about the play Take Me Out. This YA book is not quite that, though. The protagonist's crusade for justice via a swim team comprised of motley outsiders makes me root against his golden-boy side. Almost every character trails an after-school special's worth of trauma behind him, but because we learn all of this in summary, the horror stories are maudlin rather than meaningful. Whale Talk has something to say about the motivations behind redemption and revenge, but it could take a lesson in subtlety from the sonar messages broadcast by the whales of the title. (P.S. Given the protagonist's much-discussed racial struggles, whatup with the white kid on the cover?)

Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link: The straight-up fantasies in this collection--about wizards and magical handbags--are excellent examples of the genre, and I've already pointed a few fantasy-writing students to this book. But my personal loves are the stories about gangs of kids being weird and cruel and lovelorn, in which other worlds lurk just around the corner: A group of teens follows a pirate TV show (that's pirate as in radio, not as in aaarrr) that they just might be part of. A camping troop encounters a monster who's no worse than the camp bully. The theme of monsters being people too also emerges from the title story, which is probably my favorite--a dual narrative about mean girls and werewolves, with equal parts sympathy and skepticism toward both. The ending makes it seem like the story is a puzzle, but really, it's an enigma. A very pretty and delightfully monstrous one.

Comments