loftiness, existential crises and what i read in april

Pedro and Stephen just moved into a new loft in what I’m pretty sure is the exact building my friend Miah lived in until a few months ago. Maybe the building managers have a quota of sweet, stylish gay boys they have to maintain. We ate panini and fancy desserts from Bottega Louie at their place last night, and I admired how, when they have objects that don’t fit into their closets, they put them in giant matching tupperware containers. Over at our place, we put them in a pile. A neat pile, but still.

Pedro and Stephen just moved into a new loft in what I’m pretty sure is the exact building my friend Miah lived in until a few months ago. Maybe the building managers have a quota of sweet, stylish gay boys they have to maintain. We ate panini and fancy desserts from Bottega Louie at their place last night, and I admired how, when they have objects that don’t fit into their closets, they put them in giant matching tupperware containers. Over at our place, we put them in a pile. A neat pile, but still.Stephen is excited about our current book club selection, Unfamiliar Fishes by Sarah Vowell. “I guess we probably shouldn’t talk about it too much before book club,” he said, with a sneaky expression that suggested he’d be down to break the taboo if we were.

But Pedro, AK and I hadn’t read it yet, so no rules were defied. I have a lot to read in May: Fishes, a student thesis, two adoption books. I’m pretty excited about all of them, actually, but this is quickly turning into one of those periods when I need to not think too hard about all the balls I have in the air. Even though having a bunch of balls in the air keeps me from thinking about scary existentential stuff, which is how I spent last month, which is why there are two books on my April reading list by TV comediennes.

And here’s what I read last month:

How I Live Now by Meg Rosoff: This novel begins as a riff on classic children's literature, where kids get sent to the English countryside during wartime and the parents are largely out of the picture. The war in question is fraught with unanswered questions. Narrator Daisy is more interested in starving herself and pursuing her hot, psychic cousin than in understanding how and why the invaders invaded. Although this is believable, I didn't always love her generically disaffected voice. But as the hardships of war changed her priorities, the book grew on me. The plot is innovative and at times brilliantly simple, and peppered with fun quirks (see hot psychic cousin).

A House Waiting for Music by David Hernandez: This is what "accessible" poetry can and should be: razor sharp, a window into understanding that doesn't sacrifice strangeness. Anxiety, especially as related to disease and accident, hovers at the edge of these poems (or maybe that's just where my head is these days): Unacknowledged cancer is a fish caught, injured and released. Humor, cruelty and love dance with pop culture and pharmaceuticals in Hernandez's tight lines. Although a few of the poems feel like "early work" (and I think they are), the book as a whole is carefully crafted and brimming with music.

Saturday by Ian McEwan: Saturday is a long day for neurosurgeon Henry Perowne and his family, one fraught with the distant threat of the impending Iraq war and the closer-to-home threat of Baxter, a mentally unstable man whom Henry collides with in his car and, later, in his home. McEwan employed a similar strategy of exploding one life-changing day into a novel in On Chesil Beach, which I loved. Maybe I was in the wrong mood this time around, but I found the level of detail monotonous and I sympathized more with Baxter, whose world is crashing down around him, than with the privileged Perowne family, who are mostly just unnerved by the idea of the world crashing down. In making Henry's daughter a poet, I think McEwan is trying to say something about the intricate interplay of medicine and imagination, fact and possibility. But as neurology novels go, I much prefer Richard Powers' The Echo Maker.

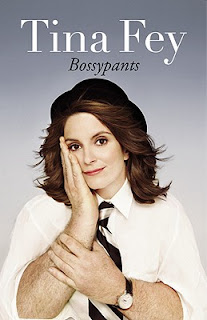

Bossypants by Tina Fey: Like Nick Hornby's A Long Way Down, this is a lighthearted book that got me through a rough time. But while Tina Fey makes not taking herself too seriously a sort of mantra (back off, feminists against photoshopping--unless you plan to take issue with all forms of physical enhancement, including earrings), the book is anything but shallow. She calls the entertainment biz on its subtle sexism without ever becoming the whining shrew that female whistle-blowers are often accused of being. (And her point is that she doesn't care if you think she's a whining shew. She is not living her life for you.) I loved her chapters on the little ways women take each other down, from drama camp competitions to child-rearing orthodoxy. I'm probably flattering myself by saying I related to her--the anxious, ambitious product of a happy childhood who wants to do right by her favorite people--but there it is.

Are You There Vodka? It’s Me, Chelsea by Chelsea Handler: Chelsea Handler is fearless, and I think that serves her TV comedy well. But on the page, her willful lack of introspection gets old fast. She's one of those people who thinks that racist jokes, if accompanied by an "I'm so un-PC!" wink, are not racist. Or maybe she just doesn't care. Although there are some funny passages about her family and her drinking habits, the book never quite settles on a tone or even a degree of realism. I'm sure David Sedaris exaggerates too, but he creates a world in which characters behave consistently if bizarrely. Handler's tone is more like truth, truth, crazy impossible lie. Her elementary school self speaks like a 30-year-old. I kept trying to figure out if that was supposed to be part of the comedy. And by the time I got to the chapter in which she and her evil drunken friends cackle their way through a birthday dinner for a girl they all hate, I just hoped I would never meet her.

Comments

I also related to much of her story. I was a little thrown that she's only 3 years older than I am, but then realized it makes sense since I get so much of her humor.

Oddly, I also have a facial scar (2 actually) from when I was young, so I found her realization that people were perhaps overcompensating for hers with praise interesting. Mine have less sinister origins, but the dog bite gets to me because my parents still treat it as my fault. Not untrue per se, but they act like they'd told me the dog next door had been abused (I don't think they did) and that I understood what that meant when I was 5. Um, no. All of which, of course, says more about me than Tina Fey and her scar.

Here's another take on Fey's treatment of sexism in the book which also feels accurate from a tv comedy writer.