book/clubbing, bitchiness and what i read in january

Here’s a Note To Self that I have to write to myself over and over: Don’t try to do a zillion things in one day. It will make you bitchy. Yesterday I cleaned the house, including the billows of cat hair under the bed (made me miss T-Mec, in all her furry glory); went to My Life is Poetry, a reading of work by LGBT seniors (inspiring!); went to book club (debate-y!); and went dancing in WeHo (Britney-y!). Each thing was fun on its own, but I was pretty much exhausted from 4 p.m. on. When I was trying to wrap up book club so we could meet Nicole and Kimberly and friends in WeHo, I kept hushing side discussions so we could choose the book for next time. Two people kept talking, so I just stared at them until they were quiet.

Here’s a Note To Self that I have to write to myself over and over: Don’t try to do a zillion things in one day. It will make you bitchy. Yesterday I cleaned the house, including the billows of cat hair under the bed (made me miss T-Mec, in all her furry glory); went to My Life is Poetry, a reading of work by LGBT seniors (inspiring!); went to book club (debate-y!); and went dancing in WeHo (Britney-y!). Each thing was fun on its own, but I was pretty much exhausted from 4 p.m. on. When I was trying to wrap up book club so we could meet Nicole and Kimberly and friends in WeHo, I kept hushing side discussions so we could choose the book for next time. Two people kept talking, so I just stared at them until they were quiet.

“Sorry, I went all teacher on you,” I laughed.

“Yeah, I can totally tell you’re a teacher!” said Sunshine, a new member.

“I’m not a teacher,” I snapped.

Anyway, here’s what I read in January:

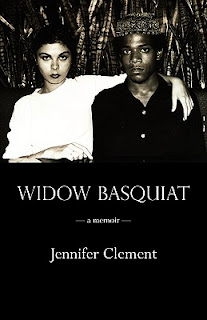

Widow Basquiat by Jennifer Clement: An odd and great little book that makes me want to write in short, simple sentences. It's part memoir--with apparent transcriptions from Suzanne, Basquiat's longtime girlfriend, that grow in length and frequency as she grows as a character--and part prose poetry. The story of Suzanne and Jean-Michel's love affair is one we've seen before: troubled genius meets troubled, ambivalent muse. It's nice to hear from the latter in her own voice (and that of her friend, author Jennifer Clement, who appears as a character only late in the book), in such lovely, nonjudgmental prose. Suzanne, like Jean-Michel, knows all the intricacies and vulnerabilities of her own skeleton. In this way, the book is an X-ray: just a glimpse, but one that looks deep.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot: The stories of Henrietta Lacks, a poor African American woman who died of cervical cancer at age thirty, and the cells from her tumor—-which were kept alive and continue to be used in countless medical studies—-intertwine like DNA. Rebecca Skloot is a hell of a storyteller and, if you’re a hypochondriac like me, this book is as compelling as a horror novel. The medical establishment treated patients, especially poor people of color, abominably—-and my use of the past tense is probably unwarranted, despite some significant changes in policy since Henrietta’s death in the 1950s.

Nevertheless, Skloot acknowledges that much of the research was done in good faith, and it’s hard to argue with the results (AIDS medication, the HPV vaccine, etc.). So I get tangled in a mental time machine: X shouldn’t have happened, but if it hadn’t, Y would never have been born, so does that mean X was a good thing? Sort of?

But I think Henrietta’s daughter Deborah left the strongest impression on me, and clearly on Skloot too. Like her mother, Deborah is poor and uneducated, and she bears the psychological scars of a difficult life. Her paranoia that someone might kill her to use her body in medical tests is both crazy, completely understandable and, for me, relatable—-there but for some therapy and a few undergrad science classes go I. But she takes it upon herself to learn about her mother and her sister, who died in a “Hospital for the Negro Insane” (every bit as horrible as it sounds), and to find a sliver of peace. I’ll consider both Deborah and Skloot heroes for a long time.

The Lacuna by Barbara Kingsolver: This is one of those epics that's about everything (art, love, food, the Red Scare, cultural relations between the U.S. and Mexico, etc.), so it's hard to know where to start. Most of all, I think, it's about the way stories can both betray us and save us, and how personal stories become history. Harrison, the main character, is a mild-mannered sometime cook and typist for Frida Kahlo and Lev Trotsky. Against the odds, he becomes a celebrated author in the U.S. in the 1940s, only to have his life and his love for America shattered by the Communist witch hunts of the late '40s and '50s.

Despite being 1) a book about a writer, 2) a semi-epistolary novel and 3) one of those books in which an ordinary person is always colliding with famous people--all pet peeves of mine--I loved it. Mostly of the beautiful language and because Barbara Kingsolver puts in the legwork. She lays out the details of Harrison's early life so meticulously that when the authorities twist them around, we're as baffled and outraged as he is. I particularly liked Kingsolver's characterization of Frida as a funny, blunt, outraged woman--it reminded me that her work goes much deeper than something that looks cool and colorful on a tote bag. I also liked Violet Brown in the Nick Carraway position (that is, if the Great Gatsby was so humble he rarely used the word "I"). She's a sort of radical librarian ahead of her time.

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath: I feel like I was supposed to have read this when I was 19 and angry, but I think I relate more to Esther's craziness now--the feeling that what seems so simple for others is utterly confusing and overwhelming (especially frustrating for any erstwhile overachiever). The storytelling is a little heavy-handed at times, but I loved the language. I came away inspired to write, and grateful to live in the days of SSRIs and non-suicide options for lesbians.

Comments

Amen to that.